David J. Mabberley. Memoirs of The Peter Crossing Collection No. 1. 2024. 86 pages hardback without dust jacket. Black-and-white reproductions, some colour photographs. Price AUD 55. Available by request to peter@crossings.com.au

This is a beautiful book, essential for anyone with an interest in the voyage to the Pacific Ocean of HMB Endeavour captained by Lieutenant James Cook in 1768–71 and its botanical team of Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander and especially the artist Sydney Parkinson. The main thrust is to bring to people’s attention the existence of 32 engravings acquired for The Peter Crossing Collection in 2022. They are based on drawings of plants made by Parkinson during the voyage. The set includes three drawings from Brazil, nine from Tierra del Fuego, two from Tahiti, six from New Zealand, and, from the east coast of New Holland, seven from Botany Bay, one from Thirsty Sound, one from Lizard Island and three from the Endeavour River. Four of the species drawn in New Zealand also occur in Australia. Due to the large number of plants found, Parkinson did not have time to finish many works, instead making drawings with just parts coloured, as a basis for finishing them later, but he died at sea, off Java, in 1771, leaving many unfinished.

While none of these ‘very first eighteenth-century proof engravings’ (p. 12) has been published before, colour versions of the same plates have appeared in works such as The Banks Florilegium and Joseph Banks’ Florilegium. A selection of plates from uncoloured proof engravings held by the then British Museum (Natural History) was published in 1973 in Captain Cook’s Florilegium.

Eighteen plates completed by Parkinson appear in this set. The other fourteen are from paintings by other artists employed by Joseph Banks to copy and complete the unfinished drawings. Those who worked on the plates in London were John Cleveley, James Miller, John Frederick Miller, Frederick Polydore Nodder, and an anonymous artist or artists. It is fortunate that Parkinson’s originals remain as he left them since, in some cases, the copying artist amended them slightly and not always correctly. Banks then employed others to prepare engravings for a proposed publication that did not eventuate during his lifetime. They were Daniel Mackenzie, Gerard Sibelius, Gabriel Smith, and Charles White. Those in this set are from a folio of proof engravings, probably prepared by Banks. Several proof sets were made up and distributed but the provenance of this set is unknown.

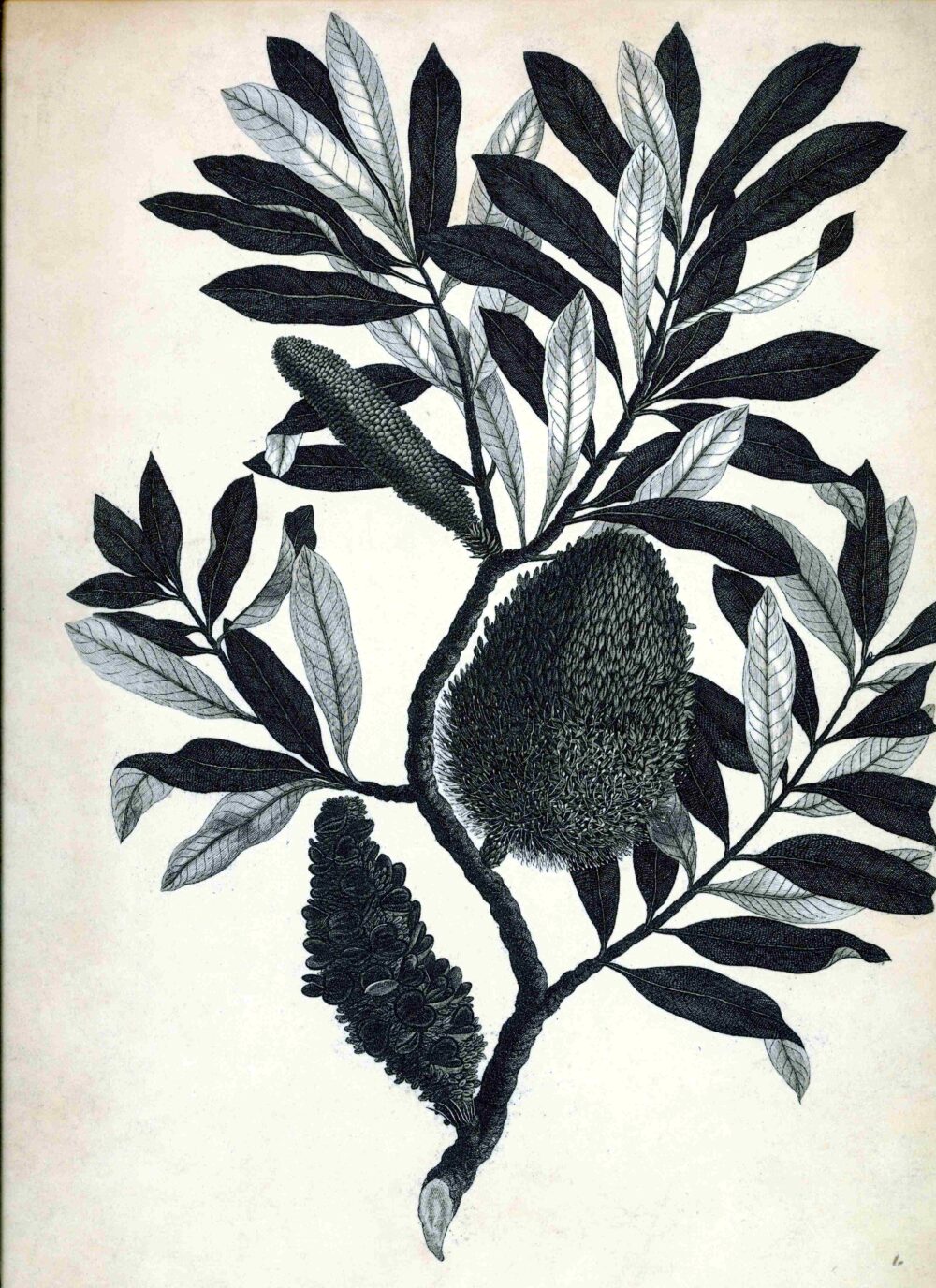

The plate of Banksia integrifolia L.f. is an example of the difficulty that the artists sometimes had in reconstructing the plant from a Parkinson unfinished original. The inflorescence is given an ovoid shape, not cylindrical as drawn correctly by Parkinson. The engraver, Charles White, has repeated the error of the unknown artist who made the first copy of Parkinson’s original sketch.

A small inaccuracy by Parkinson appears in plate 23, Lambertia formosa, the sketch of an old inflorescence at lower left showing eight pistils. This species consistently has seven flowers in the inflorescence.

For each plate, there is an account of its collection, the manuscript name given at the time (usually by Solander), then a short account of the species, the publication and derivation of its scientific name, its distribution, cultivation and uses, sometimes related species in the genus or family. Much of this is based on the entries in Mabberley’s Plant-book (2017) and Gooding et al., Joseph Banks’ Florilegium (2019). There is also a small colour photograph of the plant, usually in flower or fruit. A caption to the plate gives the current scientific name with its author and place of publication, then the size of the plate, annotations, the name of the engraver and the original watercolour, and very abbreviated references to it in print. Given the space available, it would have been good to have these abbreviations in full. An explanation of BF and JBF tucked away on p. [17] of the Introduction is a little confusing, but BF refers to Banks’ Florilegium of Alecto Historical Editions (1980–90) while JBF refers to Joseph Banks’ Florilegium of Gooding et al. (2019).

The others are not explained but refer to the country where the plant was found, with numbers from Diment et al.’s catalogue (1984, 1987) of the drawings commissioned by Banks and held at the Natural History Museum in London. Thus A (e.g. A 7/325) =Australia, B (e.g. B 15) = Brazil, NZ (e.g. NZ 2/67) = New Zealand, SI = Society Islands (Tahiti), and TF = Tierra del Fuego. There are references to plate numbers in Britten—they are to Britten, Illustrations of the Botany of Captain Cook’s Voyage … (1900–05), discussed in the Introduction but not listed in the Bibliography.

In the Introduction, Mabberley discusses the story of the acquisition of the set, the history of the preparation by Parkinson, work by other artists and engravers in London after the voyage, and the unrealised attempts to publish them. An uncoloured set of 331 plates of lithographs by Robert Morgan, edited by James Britten, was published in 1900–05; thirty appeared in Captain Cook’s Florilegium in 1973, and finally there is a passing mention to the full set published as Joseph Banks’ Florilegium in the 1980s. There is then an account of other sets of engravings—at The Linnean Society of London, a lost Berlin set, one owned by the Alströmer family in Sweden that is likely the source of those acquired by Peter Crossing, and some sent to Peter Simon Pallas in St Petersburg but now also lost.

Mabberley puts forward an argument that these proof engravings of Banksia integrifolia and Banksia serrata L.f. may have been used by the younger Linnaeus for his descriptions and therefore could be considered the types of these species, rather than Banks’s specimens. While this is a possibility, it’s difficult to prove. For the former, Linnaeus f. described the leaves as ‘subtus tomentoso-albis’ (beneath tomentose-white)—from the plate alone it would be difficult to determine whether they are tomentose. For B. serrata, he described the flowers as having ‘laminis extus pubescentibus, canis’ (laminae outside pubescent, grey)—although we have only a reproduction of the plate to examine here, the perianth limb appears to have no indumentum (it’s quite evident in a specimen), and it is unclear why he would have given a colour on the basis of the engraving and not a specimen. Parkinson’s plates can sometimes be matched to specimens collected by Banks and Solander and it would be relevant to seek such specimens for these plates. For practical purposes, regardless of which are the types, the application of the names remains the same. Should the plates be accepted as types, then they should be lodged in a public herbarium or other public collection (International code of nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) Rec. 7A)

Mabberley does not discuss the artistic quality or scientific accuracy of Parkinson’s work. Perhaps the best assessment is that of Wilfred Blunt, who wrote that ‘to place a [Ferdinand] Bauer [painting] beside a Parkinson is to be compelled immediately to admit that we are contrasting the work of a genius with that of a very competent and conscientious craftsman’ (W. Blunt in D.J. Carr (ed.), Sydney Parkinson: Artist of Cook’s Endeavour Voyage (1983) p. 40, not included in Bibliography).

A minor quibble: strictly speaking, the inclusion of ‘Sir’ in the title, and in the caption to the portrait on p. [07] (only left-hand pages are folioed), is premature. The engravings were prepared during the 1770s; Banks was not knighted until 1781 and became Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1795.

In p. [9] para 3 line 9: the Investigator voyage was around Australia, not to the Pacific, although the ship sailed home through the Southern Ocean and round Cape Horn, two years after the Australian survey finished.

There is an index to the text with the engravings but not to the wealth of information in the Introduction and descriptive texts, which therefore can be found only by reading them. The writing is sometimes rambling, e.g. p. 14, para 3, final sentence; and plate 31, para 4, second sentence. The book is printed on thick paper, which bulks out what would otherwise be a slim volume.

This is a fine addition to the vast literature spawned by the voyage of HMB Endeavour.