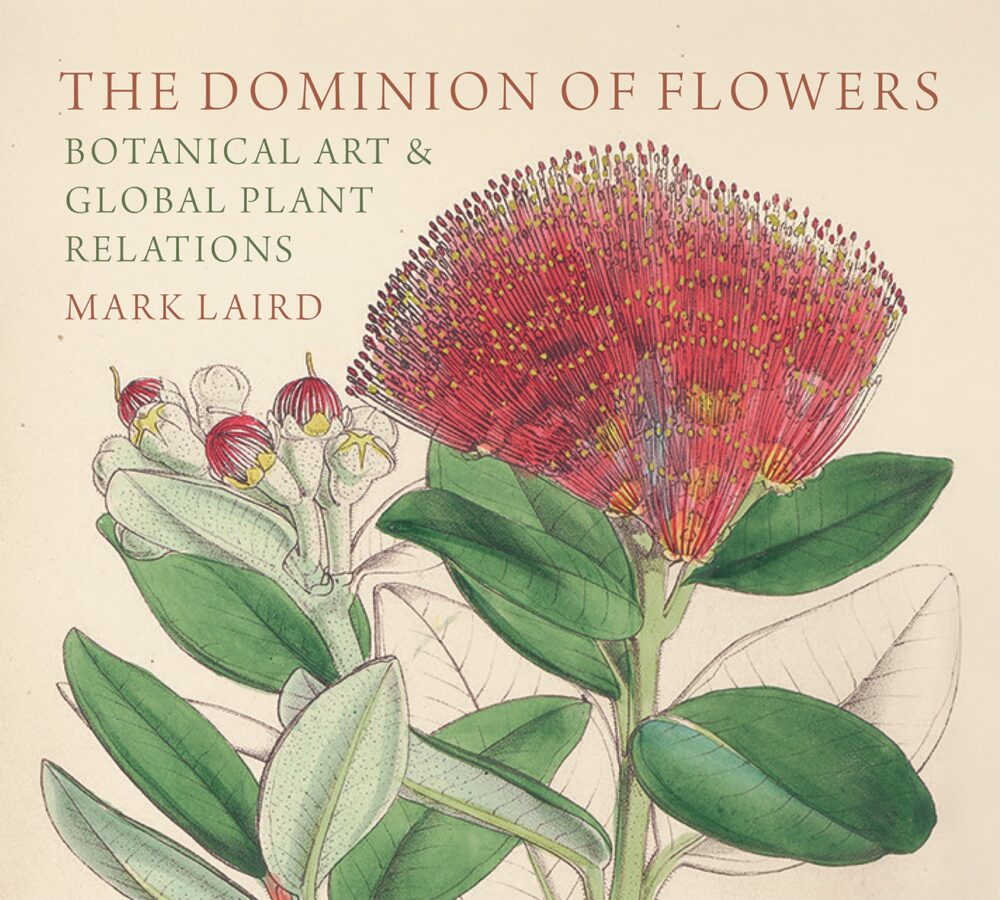

Mark Laird, The Dominion of Flowers – botanical art & global plant relations, 2024, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University Press

Mark Laird has spent 40 years restoring the pleasure grounds of Painshill Park, Surrey (UK), 18 as senior lecturer at Harvard, producing in 2015 A Natural History of English Gardening, 10 as Professor Emeritus at University of Toronto’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design.

Now he has turned his focus to New Zealand, American, African and other ‘empire’ plants that were brought to Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Dorset estates from the 1770s to the 1840s. In The Dominion of Flowers he investigates First Nations’ challenges to reconcile entwined histories with ex-colonial masters, reclaim stolen plant knowledge and agency. He also elevates the place of women as patrons, participants, players in these histories.

The book sets out whose rights were infringed in bringing ‘exotic’ novelties from afar (including sugar estates in Jamaica and Barbados). It shows how botanical art was fostered in the ‘florilegia’, albums published from 1760 to 1840. We follow the shift in the gentry’s interest in collecting exotics to commissioning artists to depict wild nature, for example in studies of Dorsetshire’s flora.

Laird also delves into family history (he has New Zealand relatives, his parents having re-migrated to the United Kingdom(UK)). He seeks ethnobotanical wisdom from New Zealand, past jobs and his North American residency.

The Dominion of Flowers is the third in Laird’s trilogy of studies, preceded by 1999’s The Flowering of the Landscape Garden – English pleasure grounds, 1720-1800, and 2017’s Mrs Delany and her Circle. It has three chapters: ‘legacies’, ‘luminaries’ and ‘ancestries’.

‘Legacies’ examines Victorian and Edwardian radicals who founded the Wildlife Trusts to protect Dorset’s local flora: the start of conservation in the UK. It also contrasts local botanising versus colonial collecting over 500 years.

‘Luminaries’ includes collectors and patrons Lord Bute (polymath founder of Kew); the Duchess of Portland (shell and plant collector); 1770s’ collage artist, Mary Delany; botanical artist J S Muller (John Miller) published in Bute’s Botanical Tables; and Phillip Miller, gardener of Chelsea Physic Garden, Director of Kew, author of the 1768 Gardeners Dictionary and 1770’s Sexual System of Linnaeus.

‘Ancestries’ tracks waves of introducing exotic plants into English gardens.

Section titles intrigue: ‘… exploitation as incubus for Heritage in England’, ‘Gender bias in World Heritage: women’s wages & plant prices’, ‘Public campaigns & penal transportation’, ‘The birth of Trusts and the 100 years since … 1921’. Or ‘Exotic or native, naturalized or cultivated: plant identities’, ‘The German and Scottish milieu in Botany and Horticulture’, ‘Plant heritage of NZ pioneers & pioneering Maori claims’ and ‘Renaming / reframing & World Heritage’. Get the gist?

Luscious illustrations reveal beauties, not least (for an expatriate kiwi) NZ plants. Botanical and butterfly images – some never before published – enliven the text. The 1770s botanical collages on black paper by Mary Delany hold their own mystery.

Underpinning Laird’s enquiry is the issue of Indigenous challenges to colonisers in New Zealand, Ecuador and Canada. He discusses the legal challenges that have given rivers ‘personhood’ (for example, Canada’s Magpie River and NZ’s Whanganui) and animal rights activism in order to question the status of plants. Are they mere chattels to exploit, export, mass-produce and consume? Do they deserve ‘personhood’? Should we reassess our interdependence with the plant world? Growing up eating kumara (sweet potato) and puha (sow thistle), climbing Pohutukawa and karaka trees, I see such plants as reflecting centuries of husbandry and understanding.

Laird argues that a personified worldview should reshape nature conservation. Given that Indigenous-managed lands cover roughly a quarter the of earth’s surface, opportunities for partnerships to reach targets for biodiversity and water conservation and First Nation’s wellbeing abound. This is also an equity issue: for the time being around five per cent of the global population that is Indigenous manages 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity.

One way forward is to draw on ideas of trust in conserving natural heritage. The book offers examples such as the Wildlife Trusts (1912) whose aim is 30 per cent of land and sea reserved by 2030, the National Trust (UK, established in 1895) and Gardens Trust (UK). Nature domains or dominions (colonies, private land) can be established through plant movement studies and with the help of influential people.

This is a fascinating book and strongly recommended. For me it underlines the point that marrying various world views is vital. And doing so is useful future-facing work.