Harriet Rix, The Genius of Trees: How trees mastered the elements and shaped the world, Vintage, 2025

The author says:

This is a story of how tree-ish trees are and how, by being tree-ish they have woven the world into a place of great beauty and extraordinary variety. It is also the story of how we both under- and overestimate trees.

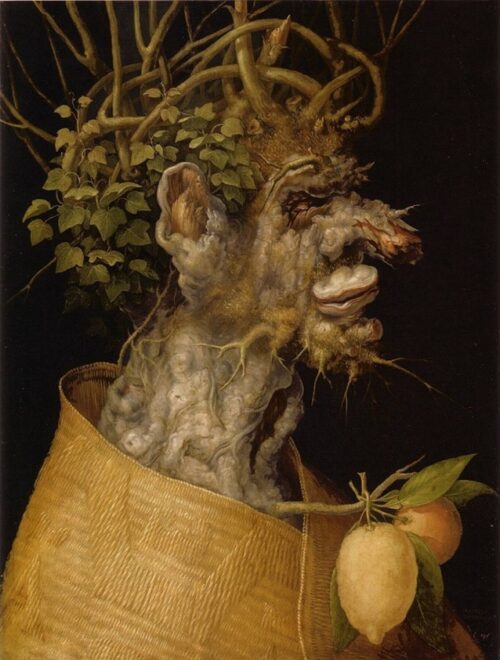

Let me be critical before I go on to praise this book. The author gives too much of what I might call ‘anthropomorphic agency’ to trees – as if the subjects in one of my favourite 16th-century painters Giuseppi Arcimboldo had come to life. But she backs it all up with mostly good sources, though often secondary or tertiary sources.

Winter, Giuseppi Arcimboldo, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Harriet Rix, who studied biochemistry, has an MPhil in history and philosophy from both the Oxbridges. She also worked in land mine clearance in the Middle East where she came across a tree that was the inspiration for this book:

I was in Iraq for work, and I saw an oak tree which had grown over a rock and was grinding it to dust, and I caught myself thinking, ‘How silly of it to grow there rather than moving onto the earth…’ Then something clicked and I realised it wasn’t silly, the tree didn’t need to move because it could work with the rock just as well as the soil. After that, everything seemed fresh evidence of the genius of trees.

She writes in a highly assertive style and, while there are a lot of footnotes in places, still not quite enough for my taste. For example, she underestimates the date of occupation of Australia by around 50 per cent, even though it is a text written very recently. On my reading this seems odd.

Nevertheless, the book is a good read, though you will have to pay attention. The author’s background in biochemistry and particularly bioenergetics is evident. She takes one much deeper into the function of trees in the environment than do Peter Wohlebben and Susan Simard, whose books on the relationships of trees have become best sellers.

Starting with the volatile organic compounds that trees send out to cause micro-seeding for rain in cloud forests, Rix takes us through a range of engineering ‘projects’ by which trees alter their own environments. She outlines the ‘biotic pump theory’ whereby huge forests like the Amazon encourage the ‘transport’ of water from humid coasts to arid interiors of land masses. This occurs not only through the 20 million tonnes per day of water they transpire, but also by the chemicals they exude with that water.

Rix works through some interesting ideas about the ability of trees to ‘manage’ fire, starting with a rare fir (Abies equi-trojanni), though my botany texts regard it as a subspecies of Abies nordmannii, growing in Turkey above the plains of Troy (see the great Farjon for naming conifers: https://brill.com/display/title/17009). The differing chemicals exuded by these trees and their neighbours, mostly pines of the species Pinus nigra, mean that, after a fire, the pines grow much faster and shade out the fir seedlings, causing the decline of the firs relative to the pines. The hot fires caused by these chemicals plus the deep beds of pine needles mean a fire can cause the pine cones to open and shed seeds into a nutrient rich ash-bed.

I have to say I take issue with some of the observations Rix makes about eucalypts and fire, and not because she hates eucalypts, though she does. She says of them ‘…it is a terrifying and toxic tree, the only one I might actively dislike…’. My concern is that her conclusions seem based on hasty research and writing. She cites the work of an ‘Australian government employee Richard Bowman’ – though I think she is referring to the distinguished academic and now professor at UTAS David Bowman – as the source of her arguments.

One of Rix’s reasons for disliking eucalypts is not quite correct. She argues that they kill off surrounding trees and other plants. This process is known as allelopathy and certainly some eucalypts (like many other plants) do this but by no means all of them. Indeed, I would guess a minority of the approximate 900 species.

So this is a book I genuinely did like in many respects even when that meant disagreeing with the author at times, but not often. Still that is in part, I hope, what people read books to do: to think!