I marvel at the way some women of the Victorian Age donned their button-up boots, picked up their long skirts and petticoats to step onto a gang plank, ready to roam the world. While many of these intrepid travellers were quite wealthy, they still had to endure the cramped quarters and rudimentary sanitation of 19th century journeys.

The botanical painter, Marianne North (1830—1890), was one such traveller. She also discovered four flower species. A pitcher plant she painted in Borneo, for example, had hitherto been unknown to science. It was named Nepenthes northiana in her honour. Between 1871 and 1885, North travelled extensively, almost always on her own. From Brazil, to Jamaica, to Japan and India, Australia and New Zealand, she visited 15 countries in 14 years, recording in her painting the people, places and plants she encountered.

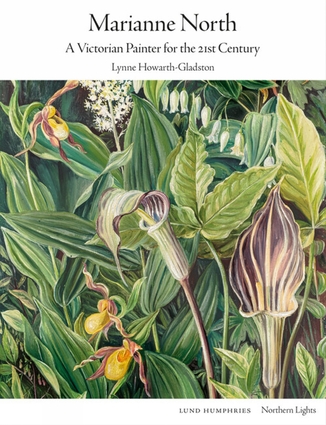

Howarth-Gladston’s biography, Marianne North, A Victorian Painter for the 21st Century (Lund Humphries, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, 2024), tells the story of North’s life as well as the development of her painting style and botanical knowledge. This makes for interesting reading. Howarth-Gladston does not go as far as those who interpret North’s work as part of current feminist and decolonial discourses. She does, however, argue that North, a woman of independent means and progressive views, produced work that is ‘highly prescient of contemporary concerns’.

The book is a handsome hardback, full of reproductions of North’s paintings. These illustrate why reception of her work since the 19th century has been mixed. Some people admire its aesthetic qualities and exactness; others see it as gaudy and amateurish. Howarth-Gladston argues for its innovativeness – botanical painting that strays from convention – and she traces its development. North admired William Henry Hunt, the watercolourist, and knew Edward Lear, the illustrator. The Tasmanian painter, Robert Hawker Dowling, introduced her to oils when spending a Christmas with the North family; oils were not usually deployed in botanical illustration. Howarth-Gladston also explains how the painstaking attention of the Pre-Raphaelite painters to detail and the arrival of photography were influences on North’s style. So too were Transcendentalist ideas espoused by the Hudson River School of painters in the United States. These artists had a deep reverence for nature and a desire to preserve the natural world and protect it from material progress. Another philosophical influence was Alexander von Humboldt, the German naturalist, who thought panoramic landscape painting could be used to express the complex interrelationships between things in nature.

North knew Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Writing to her friend Arthur Burnell, North says she thinks Darwin is ‘the greatest man living’. It was Darwin who advised her to go to Australia to see its plant life that was ‘unlike that of any other country’. Howarth-Gladston suggests North may also have been part of the worldwide network of individuals who collected data in support of Darwin’s research.

In 1880, North travelled to Australia in 1880. There she visited Ellis Rowan, whose work she admired. North was struck by the extent of introduced species in Australia, commenting that the flora of Deloraine in Tasmania was ‘far too English…it is curious how we have introduced all our weeds, vices and prejudices into Australia and turned the natives (even the fish)…out of it’. Of her visit to the Bunya mountains in Queensland, she said ‘I went rather out of my mind’ at the sight of ‘the ruthless killing of miles of noble trees’.

To house the body of work produced by her remarkable travels, North donated money to build a gallery at Kew Gardens. The architecture echoes Australian Federation style. The building was opened on 7 June 1882, in a gallery with an overwhelming array of paintings hung closely together in black japanned frames. These were arranged systematically in geographical groups and depicted each area’s flora, fauna and landscapes. While a review in the Gardeners’ Chronicle did not much like the gallery’s interior decoration, it did acknowledge that visitors will be able to acquire ‘a good idea of the natural vegetation of the greater part of the world’. It described North’s paintings as an ‘adjunct to a botanical garden’.

North’s work is not a pared down, strictly scientific representation of specimens. Rather, as one art historian has put it, it represents ‘vegetal chaos’. This can be explained by the observation of North’s sister, Catherine Addington Symonds, that she was ‘exceedingly and scornfully sceptical as to rules in art’. She ‘painted as a clever child’ who ‘had scarcely ever any artistic teaching’.

The Director of Kew Gardens, Joseph Hooker, wrote in the preface to the original catalogue of the North Gallery:

how many of the habitat’s [sic.] are already disappearing or are doomed shortly to disappear before the axe and forest fires, the plough and the flock, of the ever- advancing settler or colonist…when once effaced they cannot be pictured to the mind’s eye, except by records such as this lady has presented to us, and to posterity…We have to be grateful for her fortitude as a traveller, her talent and industry as an artist, and her liberality and public spirit.

Catherine Addington Symonds edited North’s diaries and her autobiography, Recollections of a happy life, being the autobiography of Marianne North