When I read that the AGHS’s theme for 2026 was trees I immediately thought of Capital Trees, which not only fits the theme perfectly, but which is an excellent treatise on Wellington’s trees for both locals and visitors. For those from out-of-town, Goldsmith’s book acts as a guide to the trees of New Zealand’s capital city, positioning them within the history of Wellington and discussing their significance today. My review of the book first appeared in the New Zealand Journal of Public History and is reproduced here with their permission.

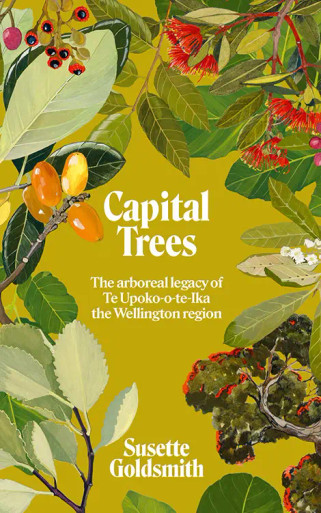

Susette Goldsmith, Capital Trees: The Aboreal Legacy of Te Upoko-o-te-Ika the Wellington Region, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2025

As both a Wellingtonian and a garden historian, I opened Capital Trees with eager anticipation and I was not disappointed. This lovely little book is a tribute to the many important trees that those of us who live in Wellington know well, and others that have contributed significantly to the landscape and history of the city.

Goldsmith, the author of Tree Sense: Ways of Thinking about Trees (2021), is well placed to bring the history and importance of the capital’s trees to the reader. Goldsmith divides her discussion of Wellington’s significant trees, both those standing and those no longer with us, into three parts with each subdivided into multiple sections by useful headings.

‘Purposeful Comings Together’ looks at the many ways in which trees have been designated as significant, the difficulties in assigning a tree the ‘heritage’ label, and the popularity of including significant trees in various lists. Researchers who have looked at properties that feature heritage trees and tried to ascertain their precise status will find this section particularly interesting. Goldsmith explains that the New Zealand Tree Register includes far fewer trees in the wider Wellington area than the combined ‘Notable Trees’ schedules kept by local councils. How these trees made it onto the lists and how much protection their listed status gives them are both thought-provoking questions. During her research Goldsmith was introduced to Te Papa’s herbarium, which although not a list is ‘a purposeful coming together of names’, so considered to be part of ‘Wellington’s arboreal heritage’. The herbarium contains 350,000 specimens of plants native to, or introduced to, New Zealand. The collection continues to grow and there is a photograph of one of the most recent acquisitions, the specimens of hard beech or Fuscospora truncata collected as late as 2018.

‘Native Trees and Fake Native Trees’ considers the types of trees that are deemed to be significant. These include those native to the Wellington area, those native to New Zealand but introduced to Wellington, and exotics – trees brought in from other countries. The history of how the pōhutukawa came to be so prominent in Wellington was particularly interesting given the controversy surrounding their presence in the city in the past few years. I wonder how many of us have heard of ‘Pohutukawa Mac’, better known as John MacKenzie, the first director of Wellington’s Parks and Reserves, who so loved the pōhutukawa that in 1941 he claimed that 200,000 of them had been planted in Wellington since his appointment in 1918. The contribution of the Wellington Beautifying Society to the glow of red that Wellingtonians enjoy each summer is also acknowledged. The Society was formed in 1935 and its members planted an incredible 6,552 trees in Wellington that year, many of them pōhutukawa. They even had a tree-planting club for children, who paid five shillings to belong and were each given their own tree to plant.

The final part, ‘Natural Monuments’, looks at trees planted to commemorate an event or a person, in some cases both. Many of these trees were planted to honour royalty: their visits to New Zealand or their coronations. Natural monuments to royalty are particularly prominent at Government House and in Parliament’s grounds but do appear elsewhere. Trees are still used to mark these events, as the trio of tōtara planted at the time of the coronation of King Charles III shows. The prime minister, the governor-general and the city’s mayor each planted one at Parliament, Government House and the Wellington Botanic Garden respectively.

Wellington’s landscape owes much to these ‘natural monuments’, although some are in a different location to where they were originally planted. The number of heritage trees in Wellington that have been successfully moved to save them is comforting for those of us who think that progress often means the destruction of natural features within a city.

A favourite tree of mine is the Styphnolobium japonicum or weeping pagoda in Lower Hutt, a remnant of Thomas Mason’s fabulous nineteenth-century garden, so I was pleased to see it warranted not only a mention but a photograph. Goldsmith tells us that the weeping pagoda is an ‘unintentional monument’, as it is a relic of a once great garden rather than being planted to bear witness to any event or personage. The same is true of ‘Frodo’s Tree’, a ‘gnarly pine’ on Mount Victoria, which is a noted tourist attraction for Lord of the Rings fans from all over the world.

Goldsmith writes engagingly, and the recounting of her personal experiences while researching the book is a delight. We wander alongside her as she hunts out the northern rātā in the Hutt Valley and learns about the historic trees in the Botanic Garden. We join in her sorrow at the removal of the avenue of trees in Whitemans Valley and her horror at the destruction wrought by the 2022 occupation of the parliamentary precinct, which inflicted fire damage to the site’s numerous pōhutukawa and necessitated the replacement of 2,500 plants.

Capital Trees is very much a Wellington publication. Written by a Wellingtonian, it is published by the capital’s Te Papa Press and features the artwork of the city’s most well-known botanical artist, Nancy Adams, whose work appears on the cover and throughout the book. Adams worked as a curator for what is now Te Papa, and contributed much to the institution’s herbarium. The book is liberally illustrated with colour photographs and includes a list of books for further reading. It would make a welcome addition to the bookshelves of tree lovers or those interested in Wellington or garden history. Slightly smaller than A5, its size makes it perfect to slip in a bag to be used as a guidebook for those wanting to explore Wellington’s significant trees. It is a delight to dip into or to read cover to cover.