Seasonal Climate Outlook April 2024 to June 2024 published by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. NIWA’s mission is to conduct leading environmental science to enable the sustainable management of natural resources for New Zealand and the planet.

‘Climate change has well and truly arrived in New Zealand and is affecting the climate where we live’ is the conclusion of a report Our atmosphere and climate 2020 released by New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ. Annual average temperatures are rising, as is the trend of an increasing number of heatwave days and decreasing number of frost days. In the surrounding waters, changes in ocean currents has seen a decline in eels, a prized resource for Māori peoples. Bird habitats in cooler areas are also at risk. By 2040, days with very high or extreme fire danger are projected to increase by an average of 70 percent, due to hotter, drier, and windier conditions.

How do such changes affect historic gardens in New Zealand? Clare Gleeson sought to find out.

Approach

My approach in assessing how climate change has affected historic gardens in New Zealand was to use three categories of heritage plantings in gardens created in New Zealand after European settlement. Although Māori were gardeners of food and haraheke (flax), as far as I could establish there are no historic Māori gardens.

The categories were firstly the botanic gardens that had been established from the early days of European settlement, secondly the gardens belonging to historic properties owned and managed by Heritage New Zealand (New Zealand’s equivalent of the National Trust) and thirdly, the privately owned heritage properties with an associated garden. It has been difficult to elicit feedback from many of those I approached so this is a truncated response to the task I set myself and it should be borne in mind that the resulting themes are a synthesis from very few gardens, although I believe they would apply to many more.

New Zealand’s geography

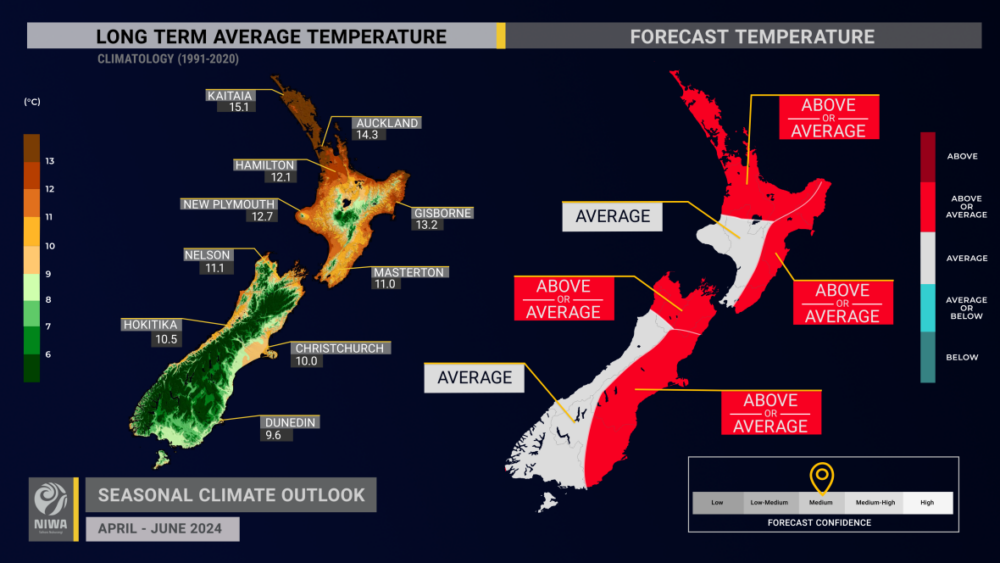

New Zealand is made up of two main islands. The distance between Cape Reinga at the top of the North Island, to Bluff at the bottom of the South, is approximately 1,300 kilometres, resulting in a number of different climatic zones across the country. Looking at the extremes, Auckland, near the top of the North Island is sub-tropical, whereas Dunedin, near the bottom of the South, has a climate more reminiscent of Edinburgh, which it was named after. Traditionally Auckland gardeners have been able to grow such delights as hibiscus, palms, bromeliads, and other plants associated with the South Pacific and other sub-tropical climes, whereas the southern gardens are perfect for peonies, trilliums and those plants that require a harsher winter. The many other cities and towns in between each has climatic benefits and drawbacks. Christchurch has always been known as the garden city, while Wellington with its frequent and strong winds makes gardening challenging.

According to Our atmosphere and climate 2020:

the national average temperature has risen by 1.13 (±0.27) degrees Celsius since 1909, at an average rate of 0.10 degrees per decade. That rate was 0.31 degrees Celsius per decade in the past 30 years. Changes in rainfall – particularly extremes – are beginning to emerge. In early 2020, Auckland experienced its longest dry spell of 47 days, well above the average length of 10 days for 1960–2019. Climate changes are translating to effects on the physical environment. New Zealand’s mean relative sea level has risen by 1.81 (±0.05) millimetres per year on average since records began more than 100 years ago, and the average rate for 1961–2018 was twice the average rate for the time period since records began to 1960.

The historic gardens

When assessing the impact of climate change on historic gardens, it is necessary to take existing factors into consideration. Although the European settlers brought with them seeds and cuttings from ‘Home’, the resulting plants’ chances of survival would have been mixed even 100 years ago due to the differences between New Zealand’s climate and Britain’s. The range of climatic regions within New Zealand itself was another challenge. This was an observation made by Martin Keay, the longtime gardener at Highwic, a Heritage New Zealand property in Auckland:

I have a sense that the garden at Highwic has never been a plantsman’s garden and that many of the earlier introduced plant varieties would have been very unlikely to have succeeded due to their unsuitability to the Auckland climate.

The manager of Fyffe House, the remnant of a whaling station in Kaikoura, first established in 1842 and registered with Heritage New Zealand in 1993 said of its garden:

Regardless of climate change it is and always has been, very seasonal and subject to droughts and to salt spray depending on the seas and wind directions which vary annually.

Of the 11 Heritage New Zealand properties that have a garden, most have been planted since being acquired by Heritage New Zealand from the 1970s onwards and many very recently, such as Kate Sheppard House in Christchurch. There is no central body responsible for the gardens in the organisation; each property is managed individually and that includes the garden. Heritage New Zealand does manage a National Heritage Preservation Incentive Fund (NHPIF), which provides funding for the conservation of privately owned places on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero (the List). Among the activities supported by the annual grants is ‘conservation work to heritage places to increase resilience and respond to the impacts of climate change, including repairs, and site stabilisation relating to land and archaeological sites.

Nevertheless, many managers approached felt they could not offer anything of use to this project. At Alberton (NZH) the manager said:

There has been a lot of planting within the garden at Alberton, since opening to the public in December 1973, and therefore we don’t have many historic plants to monitor.

Botanic gardens were developed in the main centres of Christchurch (1863), Dunedin (1863) and Wellington (1868) early in their European history. Auckland’s was much later (1982), although the Auckland Domain (1845) was, and remains, a significant green space in Auckland. There were also many smaller botanical gardens created including Timaru (1874), Gore (1906) and Napier (late 19th century). The ethos behind botanic gardens is to bring plants and people together; the educational aspect is very important, so some of the issues they have are unique to botanic gardens.

Established trees have been a constant in many gardens and in many instances are the only original plantings to remain. This is true for New Zealand Heritage properties and also Larnach Castle in Dunedin.

Alberton in Auckland dates from the 1870s and was acquired by Heritage New Zealand in 1973. The manager said:

There has been no noticeable impact on the garden at Alberton of climate change, except for the earlier emergence of daffodils in recent years, e.g. 2015 – 22 July, 2016 – 22 July, 2017 -13 July, 2018 -11 July, 2019 – 5 July, 2020 – 1 July 2021 – 6 July, 2022- 20 July, 2023 – 1 August. Last year it was such a wet one in the Auckland area which resulted in the daffodils not emerging until the traditional late July-early August time.

The manager of Fyffe House wrote that they have ‘not measured the effects of climate change in any way and have not noticed any definitive changes beyond our usual environmental fluctuations’. Fyffe House had very little garden when it was acquired by Heritage New Zealand and the planting has evolved to include varieties that were not available at the time the garden was established but which fit in with the overall garden style. The limited diary extracts available have been used to guide the planting. As a whaling station, Fyffe House was built on the coast and is very exposed. There was no evidence that climate change had affected the planting but:

we definitely look to include even more plants that both fit with the scheme and show drought tolerance; this is an important factor in selection…Over time curatorial decisions on the garden have favoured like plants but opted for those that require less water simply as this has always been a dry area and we are respectful of water restrictions that have come into place in our region over summer over many years.

At Highwic, the gardener notes that:

the permanent planting remains much the same, with existing plants seemingly unchanged by encroaching climate change. However, the soft planting – bulbs, perennials, and annuals has changed markedly since the original planting, due to all the newer plants being introduced, new varieties becoming readily available, and changing fashions in garden design.

As with Fyffe House’s diary records, Highwic’s policy ‘is to make few changes and to retain material listed in the old records. The only exception is the flower garden due to the “temporary” seasonal content. The garden has seen changes introduced over the years, many introduced by the garden volunteers.

In addition to these general comments on how existing plantings have survived, several themes relating to the effect of climate change on the gardens emerged.

Water

As well as the longer, drier summers, climate change has brought, New Zealand has been lashed by cyclones in recent years, decimating crops in the North Island and bringing severe flooding. For gardens both too little and too much water is a problem.

At the Wellington Botanic Garden, the planting in the display gardens is being redeveloped to be more sustainable, not necessarily featuring annual bedding as in the past but using plants which don’t need so much water. As a key component of botanic gardens, the display gardens will also be educational as it will show Wellingtonians ‘what you can do in your patch’. I was told:

Decisions have to be made as to how much we are prepared to irrigate. The garden is supposed to be a role model as well, which is another reason for the change in annual beds, they need constant watering so are difficult to sustain. There will still be a display but we’re looking at a lifespan of three to five years rather than an annual changeover. Conversely, the Lady Norwood Rose Garden, also in the Wellington Botanic Garden, has been affected by flash flooding and the existing drainage has struggled to cope. It now needs more infrastructure, or planting adaptations.

For the soft planting at Highwic:

we continue to plant our favourites on the basis that all seasons differ, and some years conditions will favour some plants more than others and good gardening practice can help conserve moisture in the soil. The Highwic garden is built on volcanic rock and many things would have failed this summer if we hadn’t had irrigation, while the well-established permanent planting seems to have come through this.

[However, in 2023 Auckland experienced a very wet, mild, sunless year and at Highwic] soft planting has really suffered, with many plants failing to flower well, while others found these conditions conducive to making exceptional growth instead. Growth has been phenomenal with things like Ficus pumila needing far more clipping.

Without a cold winter, there were many perennials with erratic flowering times (generally later in the year than usual), while trees like flowering cherries and Cydonia flowered erratically. Fruit trees, like the fig tree we have at Highwic, have also been erratic. Hotter summers have stressed even well-established plants.

Increase of fungal and other diseases

At the Wellington Botanic Garden, it is believed the changes in temperature will mean changes in fungal profiles. ’Nature will win but the question is whether it will win in a way that suits us’ says manager, David Sole.

At Highwic (Auckland) it was noted that weeds now germinate all year round, thrip thrives in a dry summer, and myrtle rust is likely to affect their pōhutukawa trees soon.

Wellington’s botanic gardens

The policy at Wellington Botanic Garden when considering the future is to look globally, not just internally. About 60 per cent of the collection – mostly plants from South and Central America – in the tropical house is threatened in the wild, so housing these will continue as places like New Zealand become refuges for some plants. With changes in climate, assessments will need to be made as to which plants now under glass would survive outside in Wellington’s climate, for example bananas. A new glasshouse to replace the Begonia House is planned and the new interpretation will align with the Eden Project. Collections will be put through assessment tools developed in Australia (see https://www.gardenhistorysociety.org.au/2024/04/changing-to-stay-the-same ) and Auckland, especially around trees, to see their response to temperature change.

With the change in climate, native trees whose natural zone was further north and which were not endemic to Wellington, such as pōhutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa, or New Zealand Christmas tree) and karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus or New Zealand laurel) were treated as weeds and removed, but as temperatures change they will be natural to the Wellington area and allowed to remain.

Other changes have been made at the Wellington Botanic Garden. Clipping, for example of fuchsias, has stopped to make the plants more sustainable. Since 2019 lawn management has altered with a change to meadow plantings that need less water and are more resilient. More biodiversity has been introduced, for example a bulb meadow (with daffodils) and lots of grass species for birds needing seeds.

Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush, also in Wellington, is New Zealand’s only native plant botanic garden. With increased humidity Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush is less able to grow alpine plants and most of New Zealand’s southern off shore island plants. The last two years in Wellington have been very wet and several haraheke (flax) plants at Ōtari have died.

Conclusion

This small sample of gardens suggest that for many custodians of historic gardens, the challenges of a changing climate are a constant, and are being met taking into account regional variations and annual climatic changes. With the likelihood of more extreme weather events and greater changes in New Zealand’s physical environment, gardeners will have to make further adjustments to the way they work to preserve the historical character of their gardens and to join global initiatives that seek to retain the planet’s biodiversity.

As with the broader New Zealand population, property owners don’t generally connect the actions they’re taking to adapt their homes with reducing the impacts of climate change (see https://environment.govt.nz/publications/property-owner-climate-resilience/). They still need more information about what actions they could take. With our public gardens beginning to take action to adapt to climate change, let’s hope they can offer private gardeners practical ideas about how to preserve their gardens, so that they too become historic.

This article is one of a series prepared for a project, Antipodean historic gardens and climate change, partly funded by a grant from the international charity, the Historic Gardens Foundation.